There’s a maxim favored by lazy journalists that say three of any incident – even something absurd, like spotting hipsters with potbellies – constitutes a newsworthy trend.

And it’s certainly weird, when you see totally unrelated instances of the same thing pop up. I don’t know that I’d be calling the New York Times for a trend piece on it (maybe if I spot a third one tomorrow), but I read two stories today that caught my eye: both of them have to do with private punishment being tacitly condoned by the government based on accusation.

Scott Greenfield at Simple Justice tackles the first one: a push, primarily in Chinese immigrant neighborhoods in Queens, among retailers to punish shoplifting by confiscating IDs and threatening public humiliation unless the person they’ve accused pays a “fine” of around $400. (“Who is a store to fine anyone?” Greenfield asks, reasonably.)

Scott Greenfield at Simple Justice tackles the first one: a push, primarily in Chinese immigrant neighborhoods in Queens, among retailers to punish shoplifting by confiscating IDs and threatening public humiliation unless the person they’ve accused pays a “fine” of around $400. (“Who is a store to fine anyone?” Greenfield asks, reasonably.)

There are a few problems with this, but the primary one is that, without due process or lawyers, you’re putting supreme authority into the hands of a figure with no accountability. From the article:

Some of these enforcement policies have recently come under fire. Last month, two Chinese immigrants spoke out after being wrongly accused of shoplifting at the New York Supermarket, a store under the Manhattan Bridge in Chinatown that posts photographs of accused shoplifters next to the cashier, behind the live crabs and eels.

One of those immigrants, Li Yuxin, said that after being accused of thievery, she began weeping in front of a crowd of shoppers. The other immigrant, Liang Huanqiong, a 60-year-old home attendant, said that false accusations of theft damaged her reputation and caused mental anguish.

The episodes made headlines in Chinese-language newspapers, and store officials apologized to the women and said they would train employees to better recognize thievery and use more sensitivity in approaching suspected shoplifters, the articles reported.

At a criminal defense firm, we’re no strangers to the idea that a person might be punished for a crime they didn’t actually commit. But in those situations, hopefully, we have the ability to fight that through process. There’s no process here – just extortion to the tune of $400. And any student of human nature should be pretty well aware that, if unchecked authority is right now granted tacit permission (“[no] complaints about the practice had been received,” says the Queens police department and D.A. office) to inflict punishment for infractions real or perceived, then two years from now, that $400 “fine” is likely to be considerably more costly and/or debasing. Absolute power and all of that.

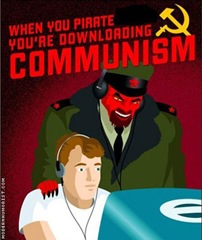

But that was just the first story I read. The second one was about the Recording Industry Association of America, which is attempting to bring a “three strikes” policy to the U.S. for Internet piracy. I lived in the U.K. when they first implemented “three strikes” (which is a weird concept, culturally, for a nation without baseball, but I digress…) for piracy. The way that it works is, after the third accusation of piracy, your ISP is required to kick you off the Internet, and keep you kicked.

But that was just the first story I read. The second one was about the Recording Industry Association of America, which is attempting to bring a “three strikes” policy to the U.S. for Internet piracy. I lived in the U.K. when they first implemented “three strikes” (which is a weird concept, culturally, for a nation without baseball, but I digress…) for piracy. The way that it works is, after the third accusation of piracy, your ISP is required to kick you off the Internet, and keep you kicked.

But again – it’s not the third conviction, just the third accusation. The RIAA has been wrong before – remember all those stories of grandmothers being sued for illegal filesharing? The RIAA is not a particularly restrained group, and its messaging has made it clear that, as much as they’re interested in seeing the right people punished, they’re also quite comfortable with going after the wrong people, if they think it’ll have a chilling effect on piracy as a whole. Since the goal is to create a cultural disincentive toward piracy, it doesn’t really matter much if they punish an actual music pirate or just someone who, say, owns a coffee shop that provides Wi-Fi that a pirate uses. As long as people are aware that punishment occurs, they’re doing their job. If the process becomes as simple as “person thrice-accused by the RIAA is then disconnected from the Internet”, and getting people disconnected from the Internet furthers the RIAA’s goal of disincentivizing piracy, then there’s little reason to be 100% certain about the accusations.

Last year, when we first began redesigning our website, I conducted interviews with all of the attorneys for their bio pages. The first question I asked most of them was, “Does the system work?” And, despite the fact that all of the attorneys here have seen the system fail people they care about, and seen punishment meted out to the innocent and guilty alike, they all gave a similar answer: “Better than any other”, or some variation thereof. There’s no doubt that we could do with a whole bunch of improvements, of course, but the alternatives that tend to get implemented – the ones that remove the system from the equation entirely – tend to treat “accusation” and “conviction” as the same concept. When you look at what people are doing outside of the system, you start to realize why it exists.