Consumerist.com pointed to this article from the Chicago Sun-Times about how stoked the police get when they find an iPhone as evidence in a case over the weekend:

Consumerist.com pointed to this article from the Chicago Sun-Times about how stoked the police get when they find an iPhone as evidence in a case over the weekend:

“When you hit the delete button, it’s never really deleted,” [Detective] Fazio said.

The devices can help police learn where you’ve been, what you were doing there and whether you’ve got something to hide.

Former hacker Jonathan Zdziarski, author of iPhone Forensics (O’Reilly Media) for law enforcement, said the devices “are people’s companions today. They organize people’s lives.”

The article talks about all of the various things your iPhone automatically does as part of its day-to-day operating system that record your assumed-to-be-private activities. Stuff like the following:

- Every time an iPhone user closes out of the built-in mapping application, the phone snaps a screenshot and stores it. Savvy law-enforcement agents armed with search warrants can use those snapshots to see if a suspect is lying about whereabouts during a crime.

- iPhone photos are embedded with GEO tags and identifying information, meaning that photos posted online might not only include GPS coordinates of where the picture was taken, but also the serial number of the phone that took it.

- Even more information is stored by the applications themselves, including the user’s browser history. That data is meant in part to direct custom-tailored advertisements to the user, but experts said some of it could be useful to police.

- Clearing out user histories isn’t enough to clean the device of that data, said John B. Minor, a member of the International Society of Forensic Computer Examiners.

- Just as users can take and store a picture of their iPhone’s screen, the phone itself automatically shoots and stores hundreds of such images as people close out one application to use another. “Those screen snapshots can contain images of e-mails or proof of activities that might be inculpatory or exculpatory,” Minor said.

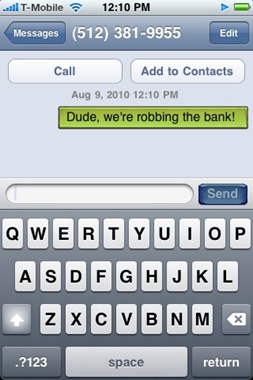

- The keyboard cache logs everything that you type in to learn autocorrect so that it can correct a user’s typing mistakes. Apple doesn’t store that cache very securely, Zdziarski contended, so someone with know-how could recover months of typing in the order in which it was typed, even if the e-mail or text it was part of has long since been deleted.

Now, most of what’s scary here isn’t that the police are going to find the text messages that you thought you’d deleted that you’d sent to your friend that read, “Dude, we’re robbing the bank!”, or that the photos that you took of yourself and your friends with the drugs, hookers, assault rifles, and bags of stolen cash charging through the bank’s lobby are going to reveal your secret location. That’s sort of a caveat emptor situation – you’re actively creating evidence of the crime in that case. What scares me is the circumstantial evidence that must pop up all the time in someone’s phone, that can be used to cast suspicion on a person’s character. Say you’ve got a Google Map that gives directions from your house to an apartment complex that’s well-known as a place people go to buy drugs. Well, why were you there? Why do you have party photos of yourself with a couple of pretty girls at the alleged Southeast Austin speakeasy from over the weekend? Why were you there? It’s not illegal to get a map to an apartment complex where people are known to buy drugs, and it’s not illegal to have pictures from a party, but all of the contextual stuff that doesn’t prove anything can still come back to get you.